Net Alert

Alert!

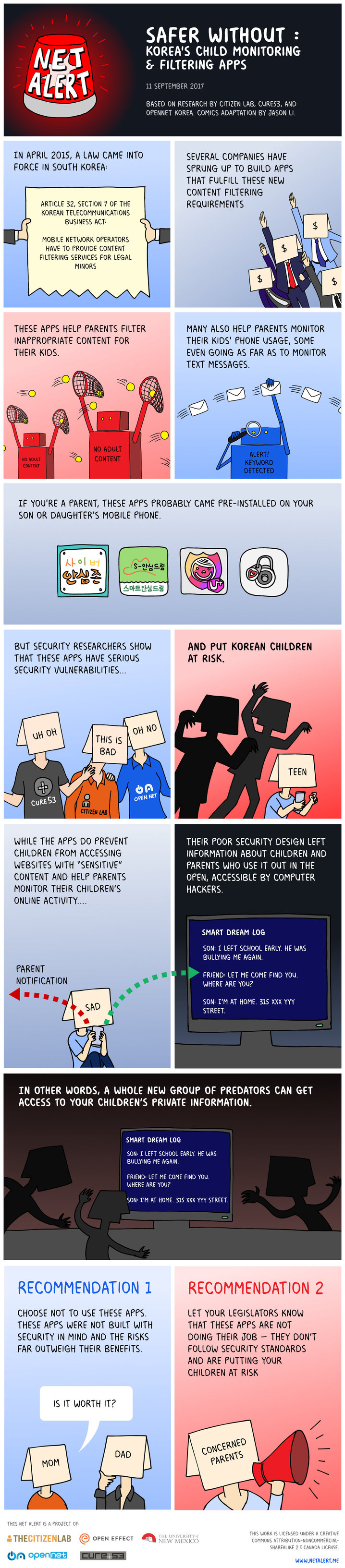

Safer Without: Korea’s Child Monitoring & Filtering Apps

Child Monitoring Apps

In April 2015, South Korea introduced a mandate that requires minors to have content filtering applications installed on their mobile phones. Security audits by Citizen Lab, Cure 53, and OpenNet Korea found that Smart Sheriff, a popular child monitoring app funded by the Korean government, had serious security and privacy issues.

This Net Alert reports on security audits of two other Korean child monitoring apps: Cyber Security Zone and Smart Dream, which found serious security and privacy vulnerabilities. These results show that apps intended to keep children safe are actually putting them at risk.

Cyber Security Zone

(사이버안심존)

Cyber Security Zone allows parents to remotely block content and monitor and administer mobile applications used by their children. The app was released as a replacement to Smart Sheriff.

Our analysis shows Cyber Security Zone is, in fact, a rebranded version of Smart Sheriff and has the same security issues that we revealed in a previous security audit.

Smart Dream

(스마트안심드림)

Smart Dream allows parents to monitor their children’s messaging applications and online search history for indications of bullying and to understand their child’s concerns and worries. If a message or search matches a database of keywords a notification is sent to the parent.

Security and Privacy IssuesClick to view descriptions for each issue. |

|

|

|---|---|---|

Man-in-the-Middle AttackCyber Security Zone and Smart Dream were vulnerable to Man-in-the-Middle attacks. A "Man-in-the-middle" attack is like the following story. Imagine trying to pass a note to your friend, but a nearby stranger takes the note out of your hand, reads it, then passes it to your friend. In a Man-in-the-Middle attack, an attacker can intercept data between where it came from and its destination allowing collection of sensitive information like passwords and logged messages. |

|

|

Sensitive Data LeakageCyber Security Zone leaked sensitive user data that could be collected by attackers including the phone numbers of parents, device ID, and the date of birth of children using the app. Smart Dream also leaked user data including passwords, logged messages, and phone numbers. |

|

|

Insertion of Fake ContentIf an attacker knows the phone number of the device that a child has installed Cyber Security Zone on, they can fake the records on the app’s server to show the child visiting web pages and installing applications that they did not actually visit or install. If an attacker knows the phone number and device ID of the device that a child has installed Smart Dream on they could send fake messages and other false information to the server. |

|

|

Phishing AttacksA vulnerability on the Cyber Security Zone user forum allows an attacker to create a fake page on the MOIBA website that could be used to steal usernames and passwords. |

|

|

Collection of all stored messagesA vulnerability in the Smart Dream API enables an attacker to collect text messages and search engine results of every child user that are stored on the service. |

|

What do Koreans think about these apps?

In an online survey, OpenNet Korea asked Koreans how they feel about child monitoring apps. Over 500 people responded and shared their views.1

Parents who use the apps were concerned about the risks of harmful information, but parents who don’t use the apps were more concerned about their children being victimized by cybercrime

What is the greater danger to smartphone-using youth: accessing harmful information or becoming victims of cybercrime? (translation)

The majority of parents thought the law should be abolished or significantly updated because the apps put children at risk.

The parental monitoring app "Smart Sherrif" exposes users to privacy and security risks such as hacking. The law requires these kinds of apps to be pre-installed on youth's phones; how if at all, should the government modify the law? (translation)

[1] The survey respondents are not a random or representative sample. The online survey was disseminated over OpenNet Korea's website, Twitter (@opennetkr), and Facebook. Respondents self-identified if they were parents.

What can you do?

Click on each group to see what they can do.

Parents

Policymakers

Developers

What can parents do?

Don’t use insecure apps

Avoid using apps that have security and privacy issues that make them unsafe. The child monitoring apps we analyzed were not built with security in mind. If an app is insecure, the risks outweigh the benefits.

Tell your legislator

Let your legislators know that these apps are not doing their job. They don’t follow security standards and are putting your children at risk. If you do not want to use child monitoring apps let your legislators know that these apps should be voluntary not mandatory.

What can policymakers do?

Make child monitoring apps voluntary not mandatory

Open Net Korea contends that the mandate requiring the use of child monitoring apps is unconstitutional, because it infringes on children’s privacy and parental rights, increases the risk of data breach, and overburdens telecoms and parents.

In December 2016 the Korean Communications Commission proposed a bill to amend the mandate to allow parents to opt-out of using child monitoring applications. The bill is currently pending at the National Assembly. This proposal is a step in the right direction as it gives parents the right to refuse to use child monitoring apps, but more can be done. OpenNet Korea argues the government should go further and abolish the mandate completely.

Ensure apps are secure

Applications designed to protect children must be held to the highest privacy and security standards. The government has a responsibility to ensure apps that are made mandatory for public use undergo independent security audits to determine if they are safe. The results of independent audits should be made public and any applications that fail to meet security and privacy standards should not be released to the market.

What can developers do?

Prioritize Security and Privacy

Developers should provide privacy and security features that give users control over their data and are enabled by default. Applications should limit the mobile permissions they use and data they collect to the minimum needed to perform the app’s core functionality. Applications should be designed according to best practices, including encrypted data storage and transmission.

Encourage Vulnerability Reporting

Independent security researchers can help developers by reporting security vulnerabilities in their apps to them. Companies can reduce barriers for reporting vulnerabilities by having clear policies and communication channels for researchers to follow and incentivize reports by paying researchers to disclose them.

Be Transparent with Users

Developers need to be transparent with users about security and privacy to ensure they are making safe and informed choices. Developers should publish easy to understand privacy policies that explain what data is collected and for what purposes, where data is stored, and how data is protected. Developers should immediately notify users if emergency security updates are issued or if data breaches occur.

Technical Reports

Citizen Lab, Cure53, and OpenNet Korea have collaborated on a series of technical audits of Korea’s Child Monitoring apps.