Net Alert

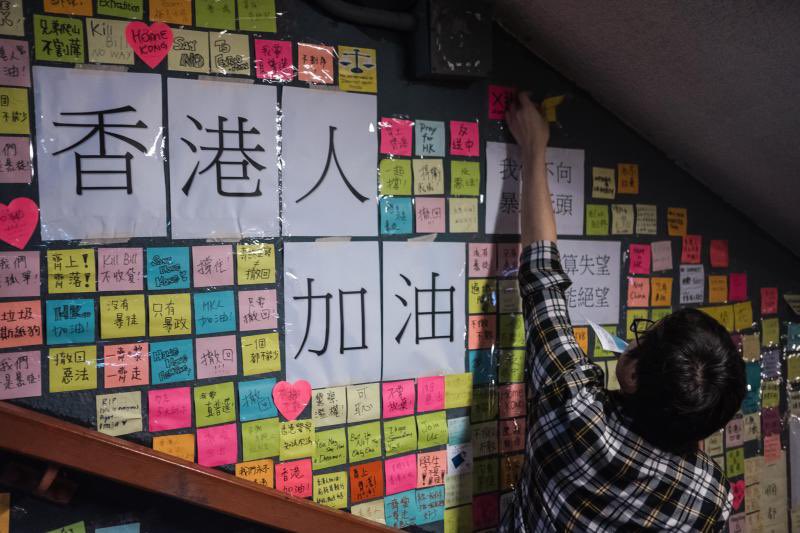

Lennon Wall

A Mosaic of Censored Images Commemorating the Hong Kong Protests

During the 2014 Umbrella Movement protests in Hong Kong, “Lennon Walls” featuring mosaics of messages and images spanned the city. Following the 2019-2020 protests, Lennon Walls re-emerged across Hong Kong in support of the protests. The name originates from the John Lennon Wall in Prague, which was created after the murder of the Beatles singer in 1980, and subsequently used to protest Gustáv Husák’s communist regime. Since the promulgation of the National Security Law in Hong Kong in June 2020, the iconic Lennon Walls have become a target of the city government. A Lennon Wall at the University of Hong Kong was taken down and barricaded following government pressure to comply with the National Security Legislation.

One of the many “Lennon Walls” in Hong Kong created during the protests

One of the many “Lennon Walls” in Hong Kong created during the protests

From June 17 to October 13, 2019, we collected images posted to Twitter related to the Hong Kong protests. We found that 26,066 of these images (8,624 unique images) were censored on Qzone, a Tencent-operated blogging platform which shares an image censorship system with WeChat, the most popular social media platform in China.1 The images include photographs, artwork, and memes documenting the protest movement. Censorship of these images is one of many examples of the Chinese Communist Party attempting to control information on the protests. Together, this collection of images forms a virtual Lennon Wall that commemorates the 2019-2020 Hong Kong protests. This post provides a high level history of the protests through the censored images.

Opposition to the Extradition Bill

In February 2019, Hong Kong proposed to amend the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation Bill 2019 (also known as the Extradition Bill) that would enable the Chinese government to detain and transfer fugitives from Hong Kong to mainland China. Concerns that the Bill could allow the Chinese government to arrest and extradite dissidents in Hong Kong motivated millions of residents to take to the streets to protest against the Bill, which ended with some of the most violent clashes between protestors and police in the history of the city.

Banners and notes left outside the Government Complex in opposition to the Extradition Bill

Banners and notes left outside the Government Complex in opposition to the Extradition Bill

Critics of the Bill argued that the law would enable authorities to arrest anyone in Hong Kong and subsequently detain them in mainland China. While the crimes punishable by the law do not include political crimes, many feared it would legalize the existing practice of abducting individuals to mainland China for political reasons.

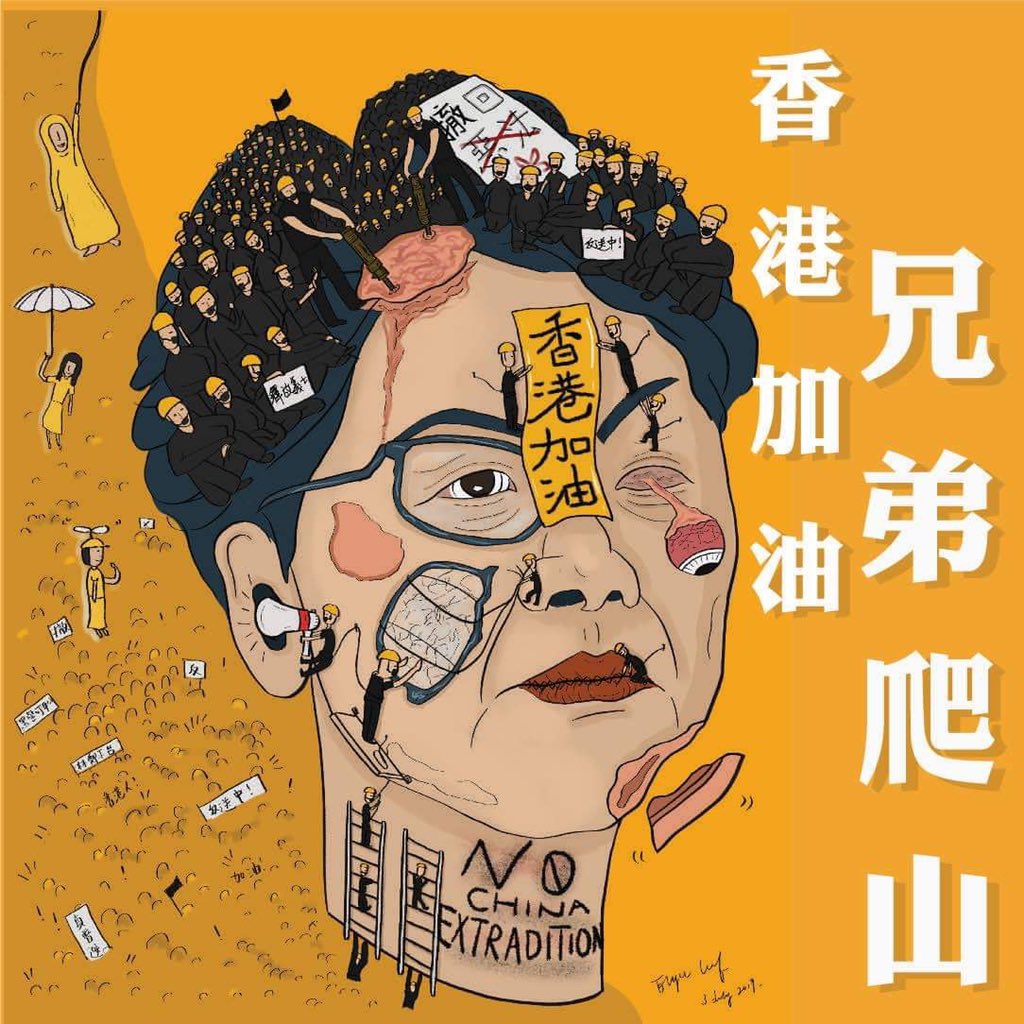

Massive Protest Movement

According to the Civil Human Rights Front, more than 1 million protesters took to the streets of Hong Kong on June 9, 2019 to oppose the proposed Extradition Bill. On June 15, Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam issued a dramatic reversal, saying she would indefinitely delay the Extradition Bill. Despite this, nearly two million people reportedly joined the march on June 16, demanding the Bill be withdrawn completely and calling for Lam's resignation.

June 16, 2019, one of the largest protests in the history of Hong Kong.

June 16, 2019, one of the largest protests in the history of Hong Kong.

Anti-extradition activist leaders said the mass of protesters was one of the largest demonstrations since the city was handed back to China in 1997.

Anti-extradition activist leaders said the mass of protesters was one of the largest demonstrations since the city was handed back to China in 1997.

An artwork created to showcase the scale of the June 16 anti-extradition protest in Hong Kong.

An artwork created to showcase the scale of the June 16 anti-extradition protest in Hong Kong.

Police Violence

The 2019 protests included some of the most violent clashes between the Hong Kong government and civilians in the history of the city, with police reporting their use of 16,000 tear gas rounds, 10,000 rubber bullets, 2,000 bean bag rounds, and 1,850 sponge grenades since June. Between June and November 2019, as much as 88% of the Hong Kong population have reportedly been exposed to tear gas.

August 31, 2019, police spraying pepper spray at protesters inside Prince Edward MTR

August 31, 2019, police spraying pepper spray at protesters inside Prince Edward MTR

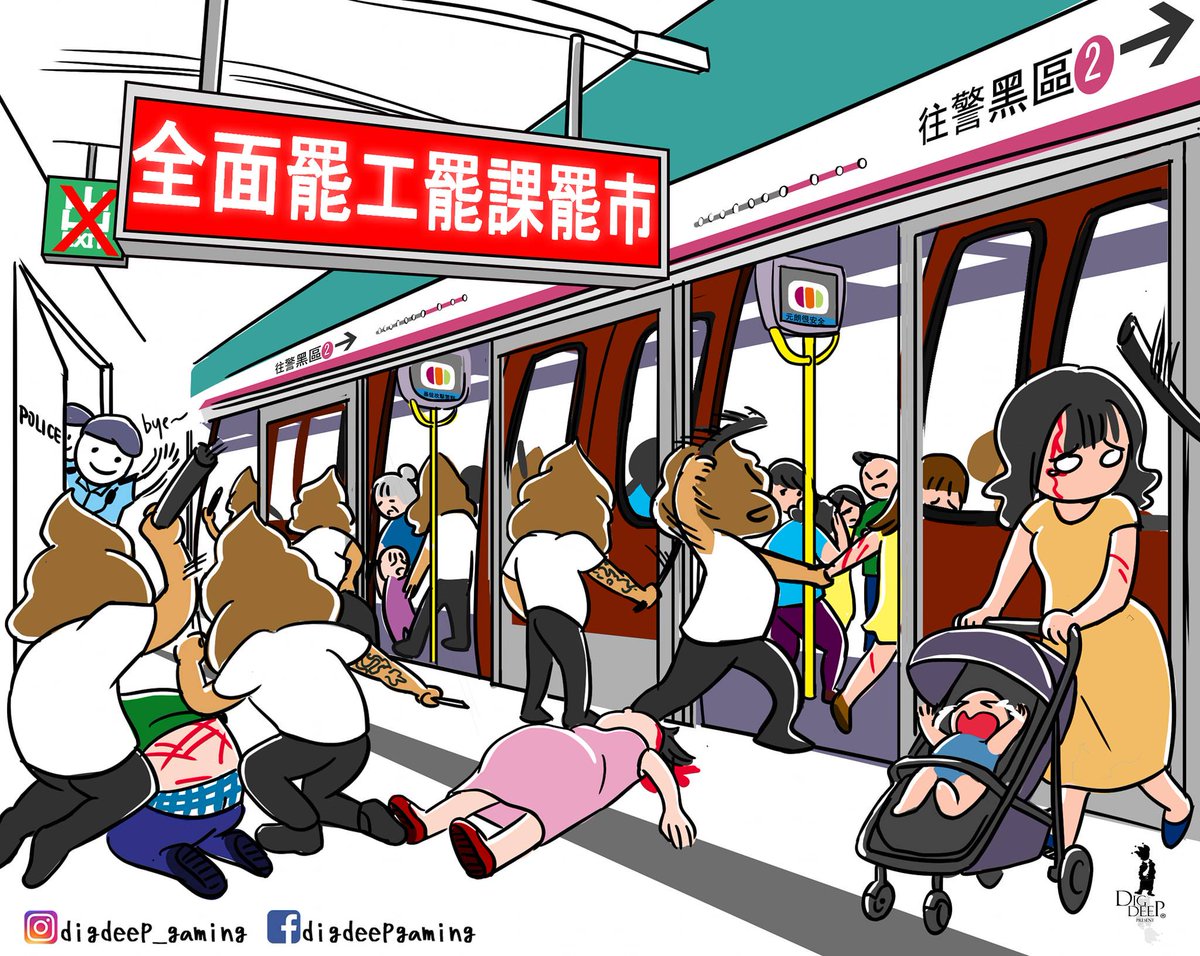

July 21, 2019, where a mob of “white shirts” attacked protesters in Yuen Long, with the police only arriving almost 40 minutes after the initial assault

July 21, 2019, where a mob of “white shirts” attacked protesters in Yuen Long, with the police only arriving almost 40 minutes after the initial assault

On July 21 2019, a mob of men armed with sticks and metal rods descended upon a train station in Yuen Long and attacked dozens of commuting protesters and bystanders alike. Many protesters remain outraged and believe the attack was highly coordinated and sanctioned by authorities. In one encounter captured by a photojournalist on the scene, members in white shirts chatted with riot police and left with a pat on the shoulder.

July 1, 2019, storming of the Legislative Council Complex

July 1, 2019, storming of the Legislative Council Complex

In some cases, anti-extradition protesters resorted to violent means to further their cause. This escalation was epitomized by the storming and defacing of the Legislative Council Complex on July 1, 2019, the anniversary of the city’s handover from British to Chinese rule. Extensive damage was wrought upon the building; portraits of political leaders were taken off the Complex’s walls and destroyed; furniture was smashed; and the Hong Kong emblem was defaced.

Psychological Strain

With mass protests and widespread police brutality occurring routinely in the city since March 2019, the emotional toll of the movement began to show with the suicide of a 35-year old protester who had strung up a banner denouncing the Extradition Bill in the hours preceding his death. The protester reportedly wore a yellow raincoat that bore the phrase “Carrie Lam kills Hong Kong.”

June 15, 2019, Site where a man committed suicide in protest of the Extradition Bill and police brutality.

June 15, 2019, Site where a man committed suicide in protest of the Extradition Bill and police brutality.

Clashes Escalate

Throughout August, many weekend protests escalated to violent clashes between riot police and protesters. Police unleashed water cannons and tear gas upon protesters who responded with bricks and molotov cocktails. The month ended with a group of riot police storming a Hong Kong subway station. Eyewitnesses recount the police targeting suspected protesters, beating these passengers with metal rods and pepper spraying within the close confines of the train car.

August 31, 2019, aftermath of the police attack at Prince Edward MTR station

August 31, 2019, aftermath of the police attack at Prince Edward MTR station

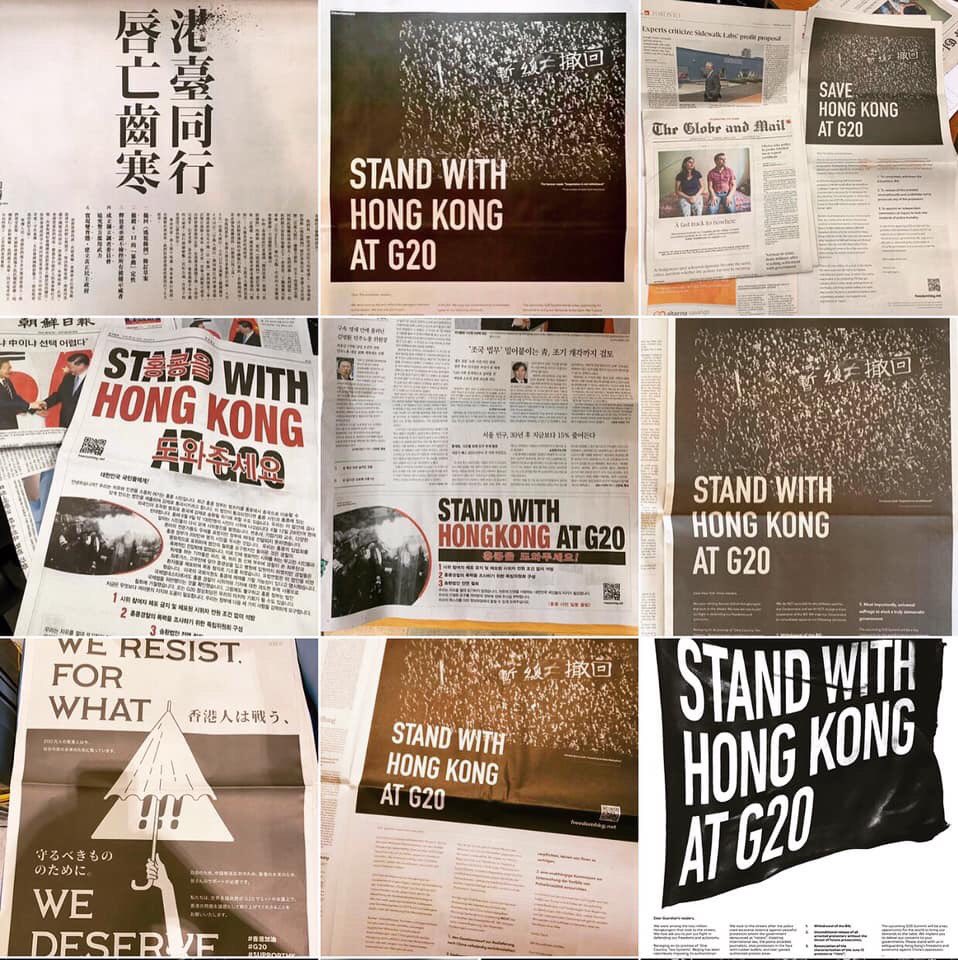

Calls for International Support

By the end of June 2019, Hong Kong protesters called on the international community and world leaders to support their cause by purchasing advertising space in foreign newspapers. In addition, hundreds of protesters in Hong Kong rallied together around foreign consulates to lobby international governments to discuss the subject of protecting Hong Kong’s special status at the G20 Summit in Osaka.

End of June, 2019, activists took out pages in foreign newspapers calling on readers to “Stand with Hong Kong at G20,” including publications in Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Canada, Germany, etc.

End of June, 2019, activists took out pages in foreign newspapers calling on readers to “Stand with Hong Kong at G20,” including publications in Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Canada, Germany, etc.

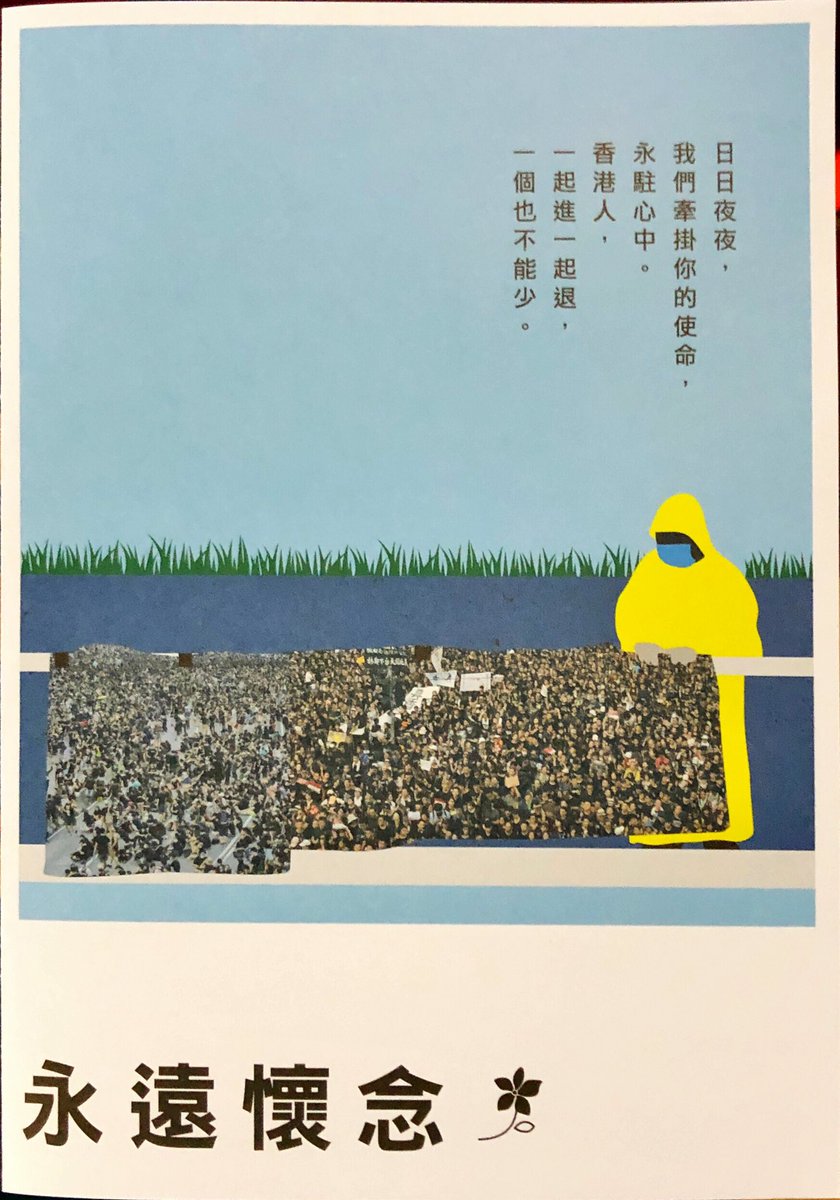

Commemorating the Movement

Amidst heavy government crackdowns, citizens and civil society groups have been creating memes, songs, and other forms of expression to commemorate the protests and preserve memory of the struggle. This art documents stories and perspectives that challenge official government narratives which often demonize the Hong Kong democracy movement.

Artwork commerating the man who committed suicide in protest, wearing his yellow rain jacket that became a symbol of dissent

Artwork commerating the man who committed suicide in protest, wearing his yellow rain jacket that became a symbol of dissent

Artwork satirizing MTR posters with images of police officers in response to the August 31, 2019 Prince Edward attack

Artwork satirizing MTR posters with images of police officers in response to the August 31, 2019 Prince Edward attack

Artwork depicting the Yuen Long attack

Artwork depicting the Yuen Long attack

Artwork depicting the August 31 attack with MTR staff closing the station and not letting medics and media in

Artwork depicting the August 31 attack with MTR staff closing the station and not letting medics and media in

Artwork depicting the Yuen Long attack

Artwork depicting the Yuen Long attack

-

Specifically, during the data collection period, we used the Twitter Streaming API to collect any tweet containing an image and that referenced one of the following hashtags: #香港, #HongKongProtest, #NoChinaExtradition, #antiELAB. We tested all such tweets’ images for censorship on Qzone, finding 26,066 images censored. From this collection of censored images, we used machine learning methods via the imagededup python library to remove duplicate images. Moreover, as we found that some tweets containing pornography referenced hashtags relating to the Hong Kong protests, we used the nudenet python library to use machine learning techniques as well as manual inspection to remove such tweets’ images from our collection. As a result of these efforts, we reduced our image collection to 8,624 unique, censored images related to the Hong Kong protests. ↩